Neutron star

Degenerate stellar remnant

A neutron star is the collapsed core of agiant star which before collapse had a total mass of between 10 and 29 solar masses. Neutron stars are the smallest and densest stars, excluding black holesand hypothetical white holes, quark stars, and strange stars. Neutron stars have a radius on the order of 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) and a mass of about 1.4 solar masses. They result from thesupernova explosion of a massive star, combined with gravitational collapse, that compresses the core past white dwarf star density to that of atomic nuclei.

Once formed, they no longer actively generate heat, and cool over time; however, they may still evolve further through collision or accretion. Most of the basic models for these objects imply that neutron stars are composed almost entirely of neutrons (subatomic particles with no net electrical charge and with slightly larger mass than protons); the electrons and protons present in normal matter combine to produce neutrons at the conditions in a neutron star. Neutron stars are partially supported against further collapse by neutron degeneracy pressure, a phenomenon described by the Pauli exclusion principle, just as white dwarfs are supported against collapse by electron degeneracy pressure. However neutron degeneracy pressure is not by itself sufficient to hold up an object beyond 0.7M☉ and repulsive nuclear forces play a larger role in supporting more massive neutron stars. If the remnant star has a massexceeding the Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff limit of around 2 solar masses, the combination of degeneracy pressure and nuclear forces is insufficient to support the neutron star and it continues collapsing to form a black hole.

Neutron stars that can be observed are very hot and typically have a surface temperature of around 600000 K. They are so dense that a normal-sized matchbox containing neutron-star material would have a weight of approximately 3 billion tonnes, the same weight as a 0.5 cubic kilometre chunk of the Earth (a cube with edges of about 800 metres) from Earth’s surface.Their magnetic fields are between 108and 1015 (100 million to 1 quadrillion) times stronger than Earth’s magnetic field. The gravitational field at the neutron star’s surface is about 2×1011(200 billion) times that of Earth’s gravitational field.

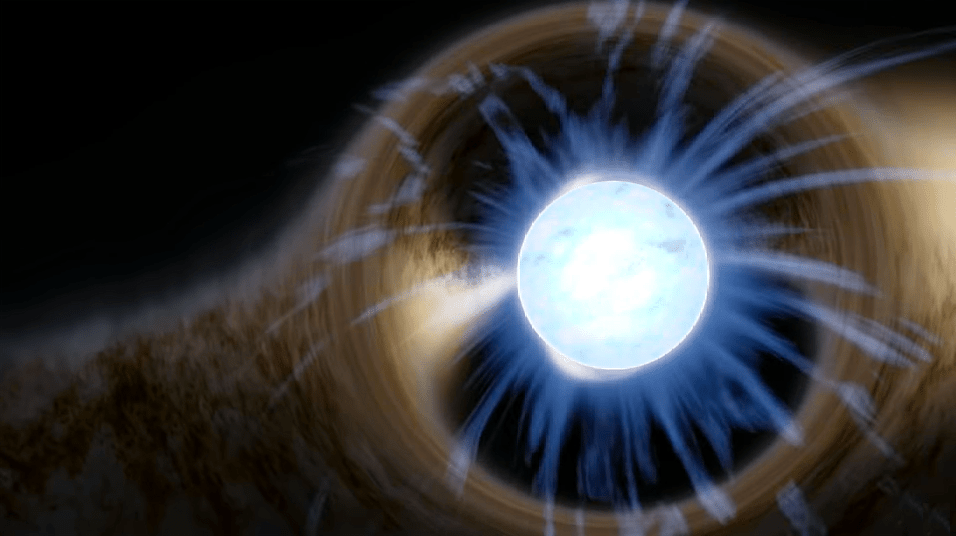

As the star’s core collapses, its rotation rate increases as a result ofconservation of angular momentum, and newly formed neutron stars hence rotate at up to several hundred times per second. Some neutron stars emit beams of electromagnetic radiation that make them detectable as pulsars. Indeed, the discovery of pulsars by Jocelyn Bell Burnell and Antony Hewish in 1967 was the first observational suggestion that neutron stars exist. The radiation from pulsars is thought to be primarily emitted from regions near their magnetic poles. If the magnetic poles do not coincide with the rotational axis of the neutron star, the emission beam will sweep the sky, and when seen from a distance, if the observer is somewhere in the path of the beam, it will appear as pulses of radiation coming from a fixed point in space (the so-called “lighthouse effect”). The fastest-spinning neutron star known is PSR J1748-2446ad, rotating at a rate of 716 times a second or 43,000revolutions per minute, giving a linear speed at the surface on the order of0.24 c (i.e., nearly a quarter the speed of light).

There are thought to be around 100 million neutron stars in the Milky Way, a figure obtained by estimating the number of stars that have undergone supernova explosions. However, most are old and cold and radiate very little; most neutron stars that have been detected occur only in certain situations in which they do radiate, such as if they are a pulsar or part of a binary system. Slow-rotating and non-accreting neutron stars are almost undetectable; however, since the Hubble Space Telescopedetection of RX J185635−3754, a few nearby neutron stars that appear to emit only thermal radiation have been detected. Soft gamma repeaters are conjectured to be a type of neutron star with very strong magnetic fields, known as magnetars, or alternatively, neutron stars with fossil disks around them.

Neutron stars in binary systems can undergo accretion which typically makes the system bright in X-rays while the material falling onto the neutron star can form hotspots that rotate in and out of view in identified X-ray pulsar systems. Additionally, such accretion can “recycle” old pulsars and potentially cause them to gain mass and spin-up to very fast rotation rates, forming the so-calledmillisecond pulsars. These binary systems will continue to evolve, and eventually the companions can becomecompact objects such as white dwarfs or neutron stars themselves, though other possibilities include a complete destruction of the companion throughablation or merger. The merger of binary neutron stars may be the source ofshort-duration gamma-ray bursts and are likely strong sources of gravitational waves. In 2017, a direct detection (GW170817) of the gravitational waves from such an event was made, and gravitational waves have also been indirectly detected in a system where two neutron stars orbit each other.

Formation

Any main-sequence star with an initial mass of above 8 times the mass of the sun (8 M☉) has the potential to produce a neutron star. As the star evolves away from the main sequence, subsequent nuclear burning produces an iron-rich core. When all nuclear fuel in the core has been exhausted, the core must be supported by degeneracy pressure alone. Further deposits of mass from shell burning cause the core to exceed the Chandrasekhar limit. Electron-degeneracy pressure is overcome and the core collapses further, sending temperatures soaring to over 5×109 K. At these temperatures,photodisintegration (the breaking up of iron nuclei into alpha particles by high-energy gamma rays) occurs. As the temperature climbs even higher, electrons and protons combine to form neutrons via electron capture, releasing a flood of neutrinos. When densities reach nuclear density of 4×1017 kg/m3, a combination of strong force repulsion and neutron degeneracy pressure halts the contraction. The infalling outer envelope of the star is halted and flung outwards by a flux of neutrinos produced in the creation of the neutrons, becoming a supernova. The remnant left is a neutron star. If the remnant has a mass greater than about 3 M☉, it collapses further to become a black hole.

As the core of a massive star is compressed during a Type II supernovaor a Type Ib or Type Ic supernova, and collapses into a neutron star, it retains most of its angular momentum. But, because it has only a tiny fraction of its parent’s radius (and therefore itsmoment of inertia is sharply reduced), a neutron star is formed with very high rotation speed, and then over a very long period it slows. Neutron stars are known that have rotation periods from about 1.4 ms to 30 s. The neutron star’s density also gives it very high surface gravity, with typical values ranging from 1012 to 1013 m/s2 (more than 1011 times that of Earth). One measure of such immense gravity is the fact that neutron stars have an escape velocity ranging from 100,000 km/s to 150,000 km/s, that is, from a third to half the speed of light. The neutron star’s gravity accelerates infalling matter to tremendous speed. The force of its impact would likely destroy the object’s component atoms, rendering all the matter identical, in most respects, to the rest of the neutron star.

Properties

Mass and temperature

A neutron star has a mass of at least 1.1solar masses (M☉). The upper limit of mass for a neutron star is called theTolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff limit and is generally held to be around 2.1 M☉, but a recent estimate puts the upper limit at 2.16 M☉. The maximum observed mass of neutron stars is about2.14 M☉ for PSR J0740+6620 discovered in September, 2019. Compact starsbelow the Chandrasekhar limit of1.39 M☉ are generally white dwarfswhereas compact stars with a mass between 1.4 M☉ and 2.16 M☉ are expected to be neutron stars, but there is an interval of a few tenths of a solar mass where the masses of low-mass neutron stars and high-mass white dwarfs can overlap. It is thought that beyond 2.16 M☉ the stellar remnant will overcome the strong force repulsion andneutron degeneracy pressure so thatgravitational collapse will occur to produce a black hole, but the smallest observed mass of a stellar black hole is about 5 M☉. Between 2.16 M☉ and5 M☉, hypothetical intermediate-mass stars such as quark stars andelectroweak stars have been proposed, but none have been shown to exist.

The temperature inside a newly formed neutron star is from around 1011 to1012 kelvin. However, the huge number of neutrinos it emits carry away so much energy that the temperature of an isolated neutron star falls within a few years to around 106 kelvin. At this lower temperature, most of the light generated by a neutron star is in X-rays.

Some researchers have proposed a neutron star classification system usingRoman numerals (not to be confused with the Yerkes luminosity classes for non-degenerate stars) to sort neutron stars by their mass and cooling rates: type I for neutron stars with low mass and cooling rates, type II for neutron stars with higher mass and cooling rates, and a proposed type III for neutron stars with even higher mass, approaching2 M☉, and with higher cooling rates and possibly candidates for exotic stars.

Density and pressure

Neutron stars have overall densities of3.7×1017 to 5.9×1017 kg/m3 (2.6×1014to 4.1×1014 times the density of the Sun), which is comparable to the approximate density of an atomic nucleus of 3×1017 kg/m3. The neutron star’s density varies from about1×109 kg/m3 in the crust—increasing with depth—to about 6×1017 or8×1017 kg/m3 (denser than an atomic nucleus) deeper inside. A neutron star is so dense that one teaspoon (5milliliters) of its material would have a mass over 5.5×1012 kg, about 900 times the mass of the Great Pyramid of Giza. In the enormous gravitational field of a neutron star, that teaspoon of material would weigh 1.1×1025 N, which is 15 times what the Moon would weigh if it were placed on the surface of the Earth. The entire mass of the Earth at neutron star density would fit into a sphere of 305 m in diameter (the size of the Arecibo Observatory). The pressure increases from 3.2×1031 to1.6×1034 Pa from the inner crust to the center.

The equation of state of matter at such high densities is not precisely known because of the theoretical difficulties associated with extrapolating the likely behavior of quantum chromodynamics,superconductivity, and superfluidity of matter in such states. The problem is exacerbated by the empirical difficulties of observing the characteristics of any object that is hundreds of parsecs away, or farther.

A neutron star has some of the properties of an atomic nucleus, including density (within an order of magnitude) and being composed ofnucleons. In popular scientific writing, neutron stars are therefore sometimes described as “giant nuclei”. However, in other respects, neutron stars and atomic nuclei are quite different. A nucleus is held together by the strong interaction, whereas a neutron star is held together by gravity. The density of a nucleus is uniform, while neutron stars are predicted to consist of multiple layers with varying compositions and densities.

Magnetic field

The magnetic field strength on the surface of neutron stars ranges from c. 104 to 1011 tesla. These are orders of magnitude higher than in any other object: for comparison, a continuous 16 T field has been achieved in the laboratory and is sufficient to levitate a living frog due to diamagnetic levitation. Variations in magnetic field strengths are most likely the main factor that allows different types of neutron stars to be distinguished by their spectra, and explains the periodicity of pulsars.

The neutron stars known as magnetarshave the strongest magnetic fields, in the range of 108 to 1011 tesla, and have become the widely accepted hypothesis for neutron star types soft gamma repeaters (SGRs) andanomalous X-ray pulsars (AXPs). The magnetic energy density of a 108 T field is extreme, exceeding the mass−energydensity of ordinary matter. Fields of this strength are able to polarize the vacuum to the point that the vacuum becomes birefringent. Photons can merge or split in two, and virtual particle-antiparticle pairs are produced. The field changes electron energy levels and atoms are forced into thin cylinders. Unlike in an ordinary pulsar, magnetar spin-down can be directly powered by its magnetic field, and the magnetic field is strong enough to stress the crust to the point of fracture. Fractures of the crust cause starquakes, observed as extremely luminous millisecond hard gamma ray bursts. The fireball is trapped by the magnetic field, and comes in and out of view when the star rotates, which is observed as a periodic soft gamma repeater (SGR) emission with a period of 5–8 seconds and which lasts for a few minutes.

The origins of the strong magnetic field are as yet unclear. One hypothesis is that of “flux freezing”, or conservation of the original magnetic flux during the formation of the neutron star. If an object has a certain magnetic flux over its surface area, and that area shrinks to a smaller area, but the magnetic flux is conserved, then the magnetic field would correspondingly increase. Likewise, a collapsing star begins with a much larger surface area than the resulting neutron star, and conservation of magnetic flux would result in a far stronger magnetic field. However, this simple explanation does not fully explain magnetic field strengths of neutron stars.

Gravity and equation of state

The gravitational field at a neutron star’s surface is about 2×1011 times stronger than on Earth, at around 2.0×1012 m/s2. Such a strong gravitational field acts as a gravitational lens and bends the radiation emitted by the neutron star such that parts of the normally invisible rear surface become visible. If the radius of the neutron star is 3GM/c2 or less, then the photons may be trapped in an orbit, thus making the whole surface of that neutron star visible from a single vantage point, along with destabilizing photon orbits at or below the 1 radius distance of the star.

A fraction of the mass of a star that collapses to form a neutron star is released in the supernova explosion from which it forms (from the law of mass–energy equivalence, E = mc2). The energy comes from the gravitational binding energy of a neutron star.

Hence, the gravitational force of a typical neutron star is huge. If an object were to fall from a height of one meter on a neutron star 12 kilometers in radius, it would reach the ground at around 1400 kilometers per second. However, even before impact, the tidal force would cause spaghettification, breaking any sort of an ordinary object into a stream of material.

Because of the enormous gravity, time dilation between a neutron star and Earth is significant. For example, eight years could pass on the surface of a neutron star, yet ten years would have passed on Earth, not including the time-dilation effect of its very rapid rotation.

Neutron star relativistic equations of state describe the relation of radius vs. mass for various models. The most likely radii for a given neutron star mass are bracketed by models AP4 (smallest radius) and MS2 (largest radius). BE is the ratio of gravitational binding energy mass equivalent to the observed neutron star gravitational mass of “M” kilograms with radius “R” meters,

Given current values

and star masses “M” commonly reported as multiples of one solar mass,

then the relativistic fractional binding energy of a neutron star is

A 2 M☉ neutron star would not be more compact than 10,970 meters radius (AP4 model). Its mass fraction gravitational binding energy would then be 0.187, −18.7% (exothermic). This is not near 0.6/2 = 0.3, −30%.

The equation of state for a neutron star is not yet known. It is assumed that it differs significantly from that of a white dwarf, whose equation of state is that of a degenerate gas that can be described in close agreement with special relativity. However, with a neutron star the increased effects of general relativity can no longer be ignored. Several equations of state have been proposed (FPS, UU, APR, L, SLy, and others) and current research is still attempting to constrain the theories to make predictions of neutron star matter.This means that the relation between density and mass is not fully known, and this causes uncertainties in radius estimates. For example, a 1.5 M☉ neutron star could have a radius of 10.7, 11.1, 12.1 or 15.1 kilometers (for EOS FPS, UU, APR or L respectively).